When Jacob spoke to his people, he read an allegory and explained it to them, but he had probably never even seen an olive tree. To Jacob, the concept of the olive tree must have been a great mystery. I imagine that Nephi was Jacob’s tutor, teaching him how to write and especially to read and understand the writings on the plates of brass. Who else could have taught Nephi’s younger brother? I suppose that at some point Nephi may have sat Jacob down and said, "Let me explain to you how olive trees grow, and how this extended prophetic allegory really works. In fact, before you were born we used to have olives on our property in the land of our inheritance." Presuming Nephi was familiar with olive horticulture, he could have passed on such knowledge—which he described earlier as "the things of the Jews" (2 Nephi 25:5)—to his brother Jacob.

Indeed, all the things that are mentioned in the allegory of the olive tree are the exact things that one needs to do to raise not just wild olives or bad, bitter olives, but to make them good. To be good olives they have to be cultivated. Unless you have actually been out there cultivating olives, it would not have the same allegorical value that it had when it was originally written by Zenos.

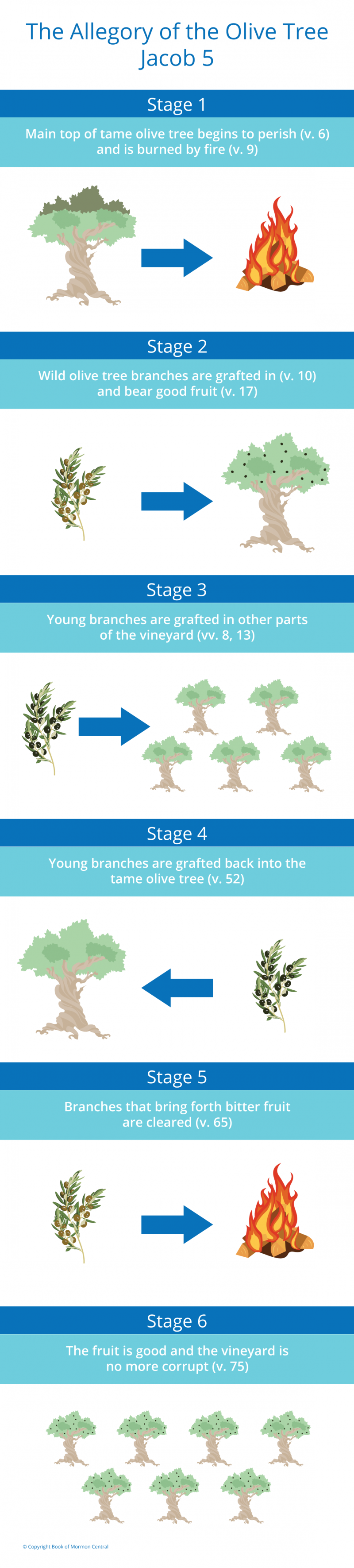

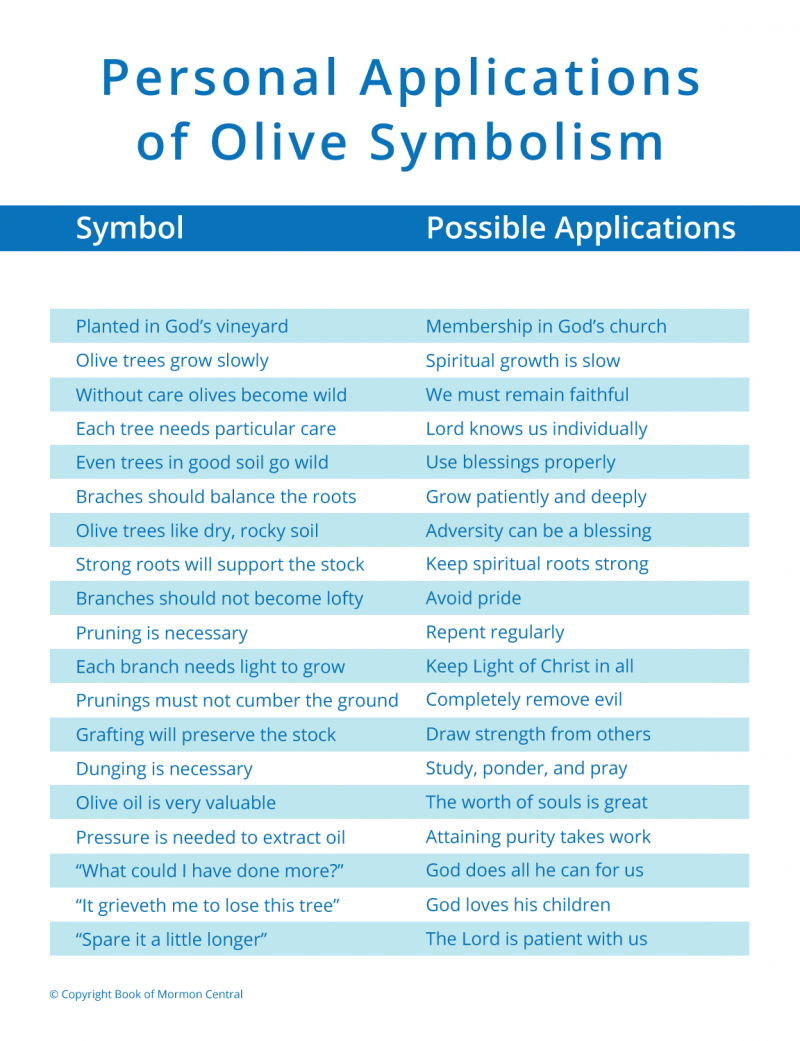

In reading this complicated and richly meaningful chapter, it helps to have some charts or a roadmap beside you. Here are three charts (Figures 1, 2, and 3) that make this allegory of the olive tree understandable, meaningful and applicable.

Figure 1 Welch, John W., and Greg Welch. The Allegory of the Olive Tree. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1999, chart 81.

Figure 2 Welch, John W., and Greg Welch. Symbolic Elements in Zenos’ Allegory. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1999, chart 82.

Figure 3 Welch, John W., and Greg Welch. Personal Applications of Olive Symbolism. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1999, chart 83.

First, this chart (Figure 1) divides the allegory into six stages. There is a lot of repetition in this text, as the steps of pruning, planting, grafting, tending, and gathering fruit are repeated over many seasons of slow and selected growth. Cultivating an olive tree is a lifetime’s work that requires considerable knowledge and expertise. But in the end, the effort is well worth the loving care of the lord of this vineyard or orchard.

Second (Figure 2), notice all of the many features that play a role in this complex allegory of God’s whole plan for the history of salvation for the covenant House of Israel. Each of these elements has symbolic value. (1) There are many trees, and indeed olive trees do not produce alone, they require an orchard, a community of trees of their same kind. These trees behave in many ways and experience various stages of life, growth, and decay. (2) There are also several key actors: the master, the main servant, many other servants, and undoubtedly lots of other workers. Raising olives is labor intensive, and so Zenos’s allegory involves these actors in many necessary and beneficial tasks. (3) There are several locations in this allegory. Some are better than others. Some offer certain helpful advantages. Others are thought to be poor spots, but they turn out to be necessary in the overall success of the orchard. All these details show the dynamic interchange between the master and his trees and his servants. The meanings of these elements remain for readers to discern by careful reflection.

Third, this chart (Figure 3) serves as an aid in applying this elaborate parable to individual parts of our own personal lives. While the tame tree in Jacob 5 clearly represents the House of Israel, it can also apply more particularly to Jacob and to his people, and just as well to all of us. Of the many possible personal applications, here is a list of nineteen elements that readers can pause and think about. See how many of these spiritual truths and needs have meaning to you.

Swiss, Ralph E. "The Tame and Wild Olive Trees—An Allegory of Our Savior’s Love," Ensign, August 1988.